2 billion-year-old African nuclear reactor proves that Mother Nature still has a few tricks up her sleeve

In Gabon, Africa, the Oklo-Reactor is one of the most intriguing geologic formations on the Earth. In two billion-year-old rocks, natural fissile materials have sustained a slow nuclear fission reaction, as found in a modern nuclear reactor.

With a half-life of 700 million years, uranium-235 is a radioactive element. Traces of it are found in almost all rocks, especially magmatic rocks, and its decay is believed to be one of the sources of Earth’s inner heat. Because it decays over time at a constant rate, its concentration in the Earth’s crust is almost everywhere the same – except in Oklo.

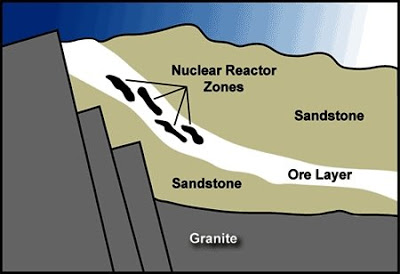

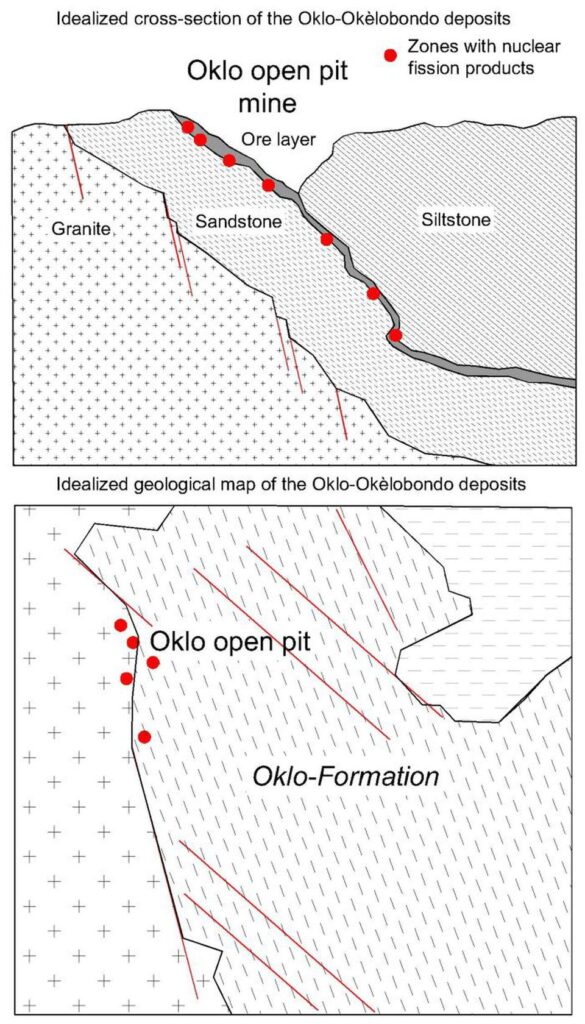

A succession of sandstone and siltstone, the Oklo-Formation, was deposited by a large river two billion years ago. Microbial activity of the first lifeforms caused the element uranium, derived from weathered magmatic rocks, to become concentrated in certain layers of the sediments. Later tectonic movements buried the layers deep underground.

In 1972, chemical analysis showed an unusually low concentration of uranium-235 in the ore mined in the Oklo open pit mine. However, there were high concentrations of elements like cesium, curium, americium and even plutonium to be found. Such elements are formed today only in nuclear reactors, as the uranium decays during controlled nuclear fission.

When uranium-235 decays, it will emit three neutrons. If one of the emitted neutrons hits another uranium atom, this atom will also decay and a chain reaction will begin. In most rocks, there is either not enough uranium to sustain nuclear fission or it decays too fast to cause a chain reaction.

In the Oklo-reactor, two factors came together to sustain slow nuclear fission for hundreds of thousands of years. Weathering of magmatic rocks and bacterial activity concentrated the uranium enough to start a nuclear chain reaction.

Then the water that infiltrated the formation along faults slowed down the emitted neutrons enough to sustain slow and stable nuclear fission. As the uranium decays, it forms other radioactive elements fueling the reactor.

Over time the Oklo-reactor has produced large quantities of toxic plutonium and cesium-isotopes, which have since decayed into stable and harmless barium. During this process, however, no harmful radioactivity has leaked into the environment.

As the planet warms due to our carbon emissions, burning oil and coal is no longer a sustainable way to meet humanity’s hunger for energy. Many experts believe that nuclear energy could be a temporary solution until renewable energy sources are ready to meet the demand.

Unfortunately, nuclear energy comes with radioactive waste. A permanent repository for nuclear waste must contain toxic elements and radioactivity for at least 100,000 years. The problem is that we don’t know what materials to use for the containers to store the waste.

Steel will rust, concrete can leak and even glass is damaged by the emitted radiation. By studying the Oklo-reactor, scientists hope to find a way to safely dispose of nuclear waste as produced by modern reactors.

Research by a team of scientists of the US Naval Research Laboratory in Washington D. C. and published in the journal PNAS has investigated how the Oklo-reactor was able to work so long and yet not pollute the environment.

In rocks recovered from the Oklo mine, barium (the ‘trace’ left by the former radioactive elements) is not found evenly distributed but rather found in nests surrounded by a thin layer of ruthenium-compounds.

Native ruthenium is a rare and inert metal often associated with ore of other elements. The scientists believe that the radioactive plutonium and cesium were encapsulated and safely isolated from the environment by a shell of ruthenium-compounds. If so, containers made of ruthenium alloys could be used to safely store radioactive waste for a very long time.

As the Oklo-reactor demonstrates, the ruthenium-compounds remain stable even if exposed to radioactivity and corrosion by water over vast geological periods.